What do I do here, anyway?

This is the translation of the keynote talk I gave at Pycon Brazil 2022. The talk was about leading complex software engineering projects and what is the major skill needed for the job

When I was invited to give a talk here, I kept thinking “what do I have to say?”. I started thinking of all I lived in these past 6 years, since my first day where my professional title was “software developer”. I looked at all the jobs I had, and kept asking “what do I do here!?”, in search of a topic I could bring to discuss with all of you.

For those of you who don’t know me, I am an oceanographer but I changed a life of studying the oceans to become a developer. Before my career 2.0, I worked at a port engineering consulting.

This company had a ship simulator that could be used to analyze the viability of a new ship to safely enter an existing port or to evaluate a new port proposal and see if it worked as it should, with the ships they had in mind.

So our job was to reproduce the tides, currents and waves, and add this and many other things into the simulator so the pilots would have a realistic environment they could try out the maneuvers. When everything was ready, we took the simulator to the ports and we had some workshops where all the stakeholders (pilots, port staff, ship industry staff, navy representatives, etc) could get together and analyse what was being proposed.

We would study and reproduce the tides, waves and currents and added them into the simulator so the pilots would have a realistic scenario to make the decisions. When everything was ready, we would take this simulator into the ports and we would have these workshops where e

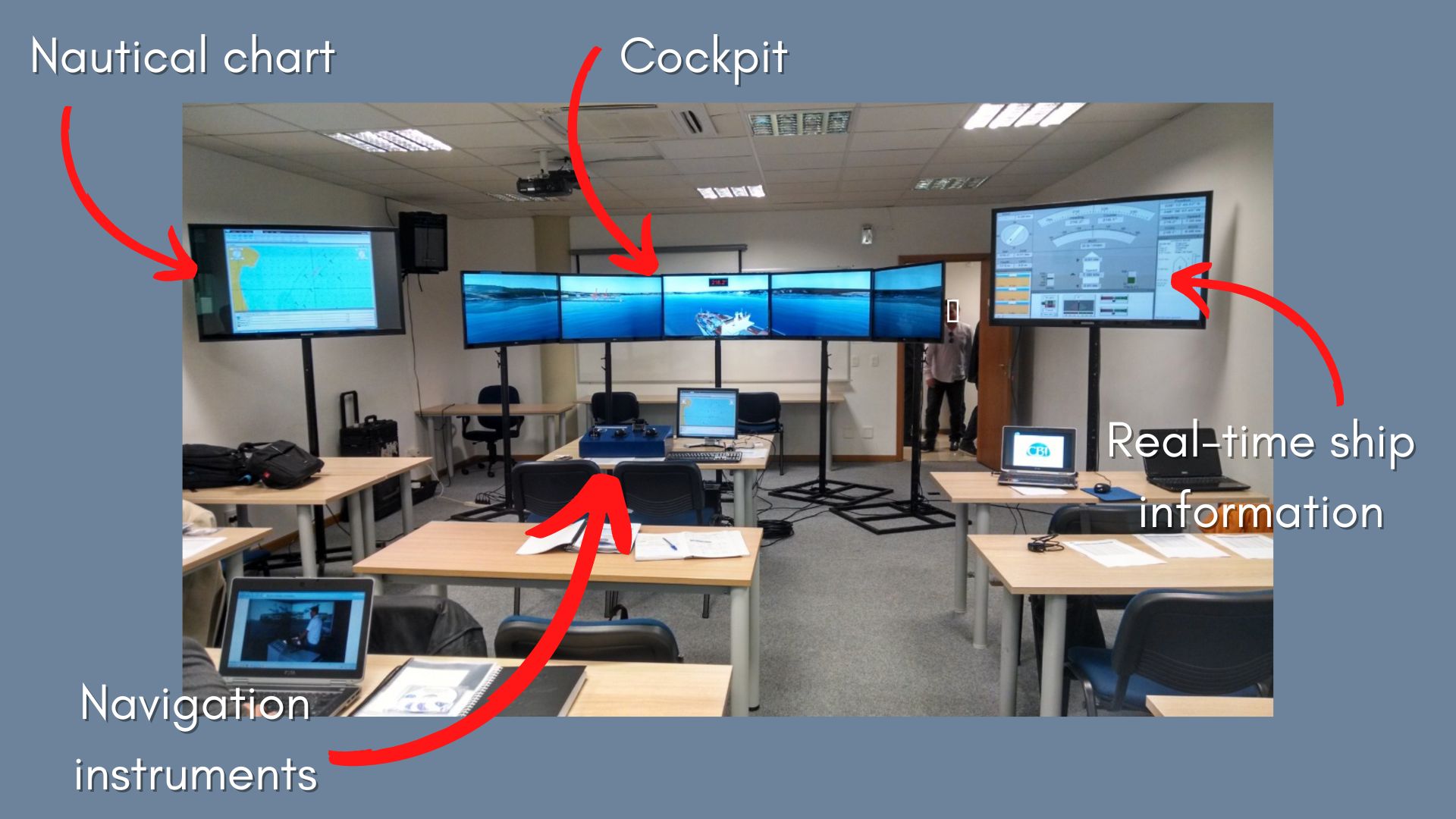

But in my first day of work, however, I knew nothing about all that. And right on my first day the company was receiving one of these workshops. For a person as newbie as I was, nothing made any sense. The workshop was like this: there were several screens. On the bottom you had the console, where you could act on the ship (change course, accelerate, etc). In one of the screens you could see the nautical charts, with the direction and speed of currents at each point in time and the channel the ship should stay in. There were also 5 screens to reproduce the view from the cockpit and a screen dedicated to several information and forces acting on the ship.

So the pilot would start a maneuver, and there we were, like 15 people in a dark room watching the screens and a ship moving super slowly. Seriously, extremely slowly. We stayed hours like this, watching the ship slowly arrive at the port. I thought that was the most boring thing in the world and couldn’t understand the reasoning. Why were those maneuvers were critical? How complex it could be given that it was so slow?

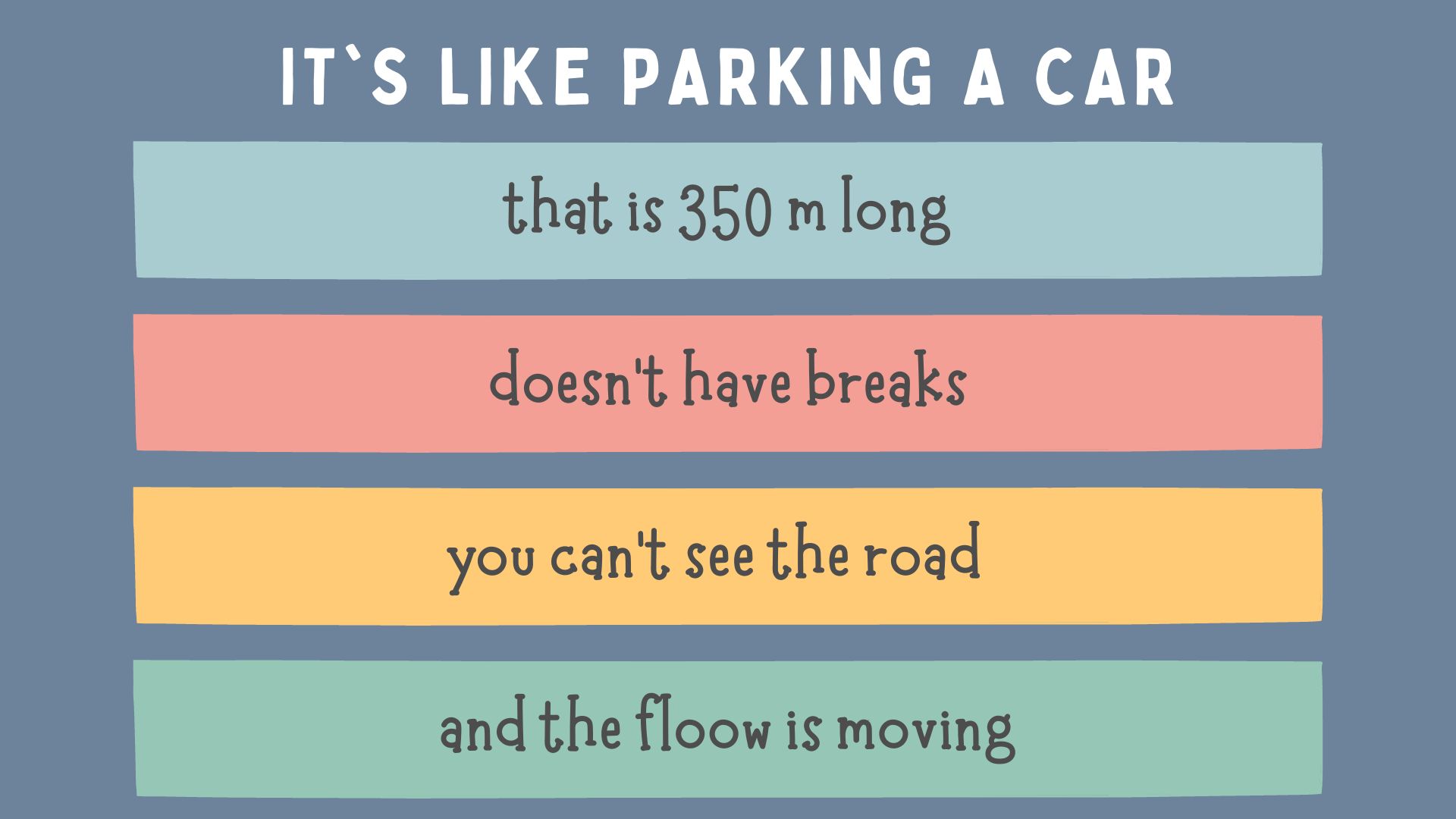

At one point I had the opportunity to talk to a pilot and ask “how hard is it to drive a ship? do we need all these people here to evaluate this?”. He replied quickly: “Yeah, it’s not complex at all. It’s like you want to park a car. But the car has 350m, it has no breaks, you can’t see the road and the floor is moving”. Ooops.

When I started to look on what I do today I realized that, in a way, what I do in my job is maneuver these metaphorical ships. The projects I work and lead are as complex as a ship being maneuvered and it’s similarly hard to explain exactly where the complexity comes from.

. . .

If we start looking more closely to our metaphorical ship, we can see some similarities.

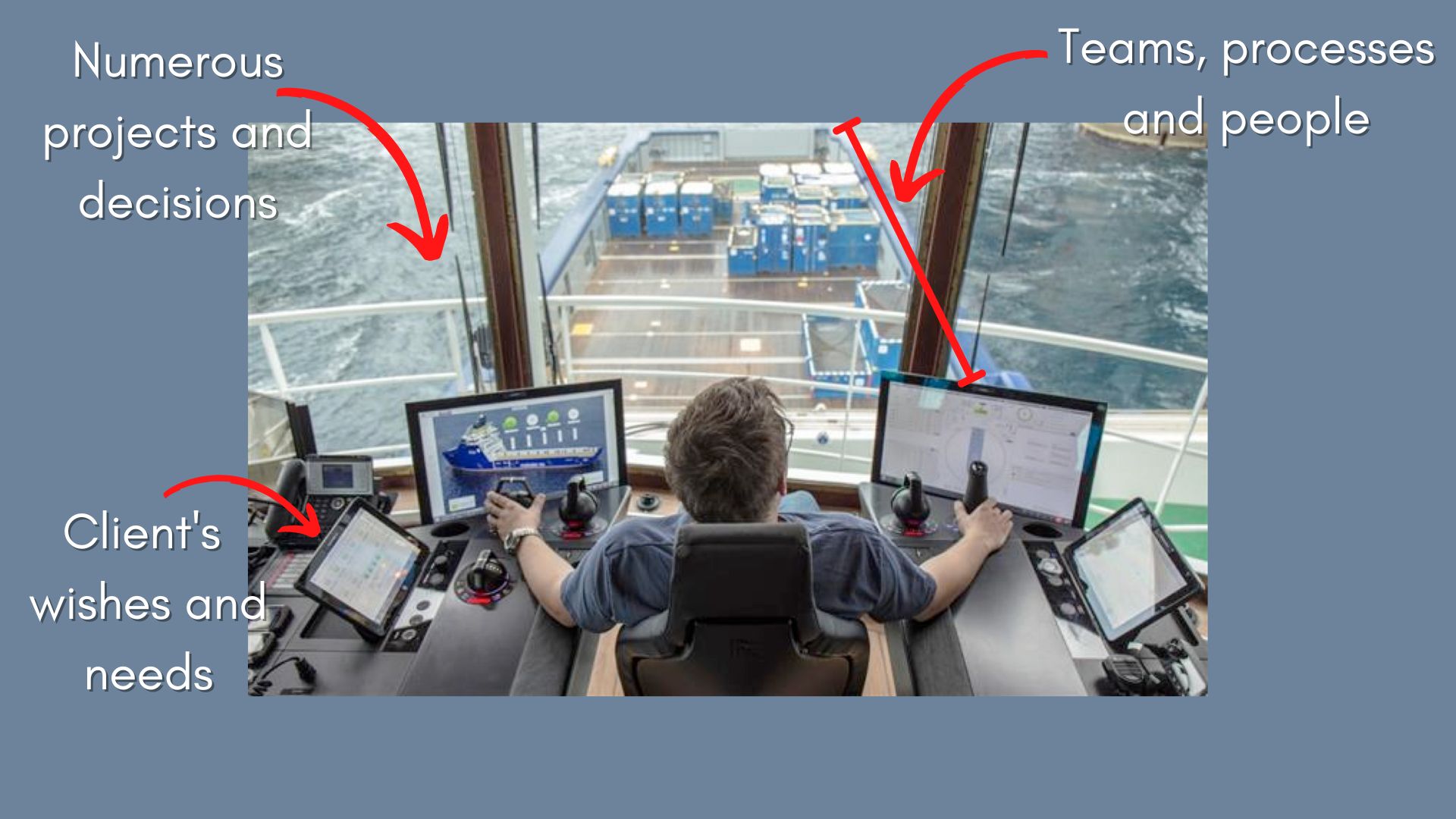

When we work in a big company, the complex projects demand a quantity of teams, people and processes that is huge. There’s a lot that have to work together to make things move forward and, similar to a ship, the inertia can be big and small changes take time to have real effect.

In a ship, we need to be constantly checking if we are in the right path since we can’t see the channel and we must rely on some sinalizations. In our world, we need to keep adjusting our course to check if we are understanding and solving our client’s needs.

The moving floor are the infinit quantity of projects, decisions and changes that happen all the time around you. There are million things happening all at once, and you need to adapt at every moment, adjusting the ship as they affect your conditions.

On my first Python meetup, when I was still working at that consulting company, people asked me who I was and what I did and I made sure to tell everyone I was not a programmer. At that time, I would only write small scripts that would help me solve some problems, and if I didn’t write big tech systems, I couldn’t call myself “programmer”.

When got asked again I had already started on my first job as a developer and still I said I had trouble calling myself a developer. The reason? I had never done a deploy.

Now, as I ask myself “what do I do here” I still have the fear that, in reality, I have nothing worth sharing to bring here. I started thinking of all the things I don’t know but think I should know before I think I am competent enough to be here talking to you.

It’s always easy to find knowledge gaps to make me undeserving of my software engineer title and doubtful of the path that brought me here. There will always be something I don’t know that can make me doubt of who I am. I will always think that what I am “missing“ to own my title is to learn this or that framework, tool, or programming language.

But thinking about the “ships” I need to deal with, I realized that these are not what my job really is about. My job is to deal with complexities, solving problems and maneuvering metaphorical ships. Code is only one of the tools I use for that.

When I started my career, I could never have imagined that I would have to and be able to maneuver these ships. As I said at the beginning, if you’re not in the cockpit, it’s very difficult to understand where the complexity comes from. When I was thinking about how best to show this and I thought the best way was to get us on a ship, so we could maneuver it together here. I want to invite all of you to really think about what you would do in each of these situations I will present to you. Really imagine yourself in that situation and think what would you do.

Let’s imagine for a moment that we’ve just joined the development team at a company called JollyCo. The company sells products from the farm directly to people in apps that customize orders directly with what people cook at home. It is a very innovative application in which people select which recipes they intend to make that week and the application assembles a list of products needed for the amount of food and people and makes an order for the products directly from the nearest farms.

In fact, we are very happy to be part of this team. The company has grown well and the product is a success, being available in Argentina, Uruguay and Chile, in addition to Brazil. All is good until one sunny day, your manager asks you to lead the product expansion project for Narnia.

Ship to be maneuvered ready to go, all aboard!

. . .

What’s the first thing you would do right now, as soon as you get into the cockpit?

I always like to start by understanding exactly where my work fits within the overall context of my team and company. Where did this request come from? From a customer asking this new country or was it a business decision? Has anyone done market research in the region? Do we have any clients in that country that we can talk to? Is there some kind of data that we can analyze to help better understand the scenario and situation?

When I started in this career, one of the scariest things was asking questions. Technical questions were daunting but business questions… seemed totally unnecessary. I assumed that if that decision was made, someone much smarter than me clearly knows what they’re doing, right?

There is a Russian saying that I really like that says: “trust, but verify”. Ensuring that the questions you have are all answered is critical to a successful project. And that goes from the intern to a senior engineer.

I’ve never heard anyone complaining “we need developers to do more code and spend less time figuring out the problem”.

It’s part of our job to ask questions. Can you imagine a pilot receiving a completely unknown ship, entering the cockpit and saying “I don’t need context, let’s maneuver this thing!” No, right? Nobody expects that and it would even be… dangerous. Spend some time getting into the cabin, looking at the nautical charts to see the route, checking the weather forecast… how are the currents today? Is there a storm coming? It’s all part of it, even if it slightly delays our departure.

Well, let’s go. We spend our first moment to understand the environment. We are confident that this project has everything to succeed. The research and business team have excellent documents explaining the context, we read the notes of interviews with local companies… all in good shape. We are confident that we understand the issue and that our main questions have been answered. Excellent! And there? What is the next step?

Well… all the documentation we read gives a business idea about the problem. It’s time to start understanding how big the problem is by looking at the code. We have to define what needs to be done and break it down into smaller tasks, define the infamous scope of the project.

But, you see… we just started at this company, we don’t have much idea of the codebase and we already have someone breathing on our neck asking when we can deliver it since that very special client who is really in need of it… ideally by yesterday. What would you do?

I think I could talk a whole lecture about scope, because this is a very difficult subject. My strategy is very simple: if I don’t really understand the area I’m going to work in, I start by asking my more experienced colleagues for help. I ask a lot of different people what problems I’m going to run into, what things they think I need to do anyway, and if there are any pitfalls I might run into that will throw all my plans off track.

And it is for these people that we will also ask the magic question: how long each of these things should take. Again, we don’t have experience with this code yet! We need to build on something. And past experience is always better than random guesses, right?

What I do when I know the project could be long, is to double the measurement. Did they say it will take 2 days? Put 4 in the planning. Did you say it will take 1 week? Put 2. If the business is going to take more than 2… better start breaking it down into smaller tasks…. if not, maybe it’s better to put more wiggle room…

Bom… toda a documentação que nós lemos dá uma ideia de negócio sobre o problema. É hora de começar a entender qual o tamanho do buraco olhando pra parte de código. Temos que definir o que deve ser feito e quebrar em tarefas menores, definir o famoso escopo do projeto.

. . .

One of the biggest fallacies in software engineering is people thinking that one day they look at a code, a light will come on and they’ll know exactly what needs to be done and how long it will take. You don’t have to do everything yourself. In fact, your job is to get things going, and if they don’t… your job is to ask for help.

So, we decided to talk to our team and everyone we talked to is confident that this project is a simple one. The product is already available in other countries, it already supports the internationalization of the documentation and the website, and the last country that was added to the system was developed a short time ago, the documentation is all up to date and the code is generic enough. The last project took just 2 months to be completed and there were no issues along the way.

We scoped the project: we have the list of tasks that need to be done and we also have an idea of where the potential pitfalls are. Is our work complete?

This is a crucial moment of the maneuver: before we start executing it, all the people involved need to be aware of where the risks and uncertainties are. It’s essential that we clearly communicate where our uncertainties are, which points concern us and what we are doing to mitigate them.

Making sure that all these points are as explicit as possible makes everyone involved in this maneuver aware that you did your best to find and mitigate these problems, and it doesn’t surprise anyone if they appear suddenly. I like to leave a lot of exposure in which areas I left a fat to compensate for the uncertainties I have and write documents to record the research and small decisions that were taken along the way.

Making all these uncertainties as explicit as possible makes everyone involved in this maneuver aware that you did your best to find and mitigate them, and it doesn’t surprise anyone if they appear suddenly. I like to be very forthcoming about which areas I left some wiggle room to compensate for the uncertainties I have and write documents to record the research and small decisions that were taken along the way.

Excellent. What now? Is it time to get yourself to work? Once you have a clear to-do list… is everything in order?

Before getting down to business, when I have a list of what needs to be done, I like to analyze which tasks are fundamental customers to use the feature and which are just cosmetic and can wait a little longer. I want to know exactly what, from this list, which may be quite long, can help me get this product into the hands of the customer as quickly as possible; even with all the limitations that may exist, whether in terms of functionality or user experience.

Not always the easiest or coolest task is the one that will help me deliver a solution first, so this prioritization helps me to keep perspective and not just focus on what is technically more challenging or interesting.

OK! We’re finally done. Time to do what we love most: write good old code!

But code is not the focus here. Of course, we could spend hours talking about this part. I’m sure there will be many other lectures at this and several other events that will allow you to improve this part.

I want to talk about something else. In this process, everyone spent a lot of time understanding what needs to be done, we defined the scope and are aware of the problems. We can say that we have everything to have a successful project, right?

Let’s say we start the project and soon after we realize that Narnia instead of using the representation of money that we use ($100), uses the money symbols to the right of the monetary value (100$), but our system is not prepared for this. What now!?

We’ll need to adapt all of our interfaces to handle this. This is definitely not going to be simple. Nobody’s sure how many interfaces and APIs present the currency as a string, so we’ll have to search the farthest corners of the system to make sure we have the changes correctly done. We can start by aligning with all stakeholders that this is a complex but ultimately aesthetic change, so we can leave it for later. Great! Crisis resolved and the ship is back on course.

A few days later we receive the information that the government of Narnia passed a new legislation that any customer has the right to cancel any order, whether it is in the state it is in (paid, or received) for up to 48 hours after the initial order. Our system is not ready for that. We will need to rewrite a good part of the refund system and we need a system to manage this return with highly perishable products, such as those that depend on a refrigerator. By our estimates, this will take at least 2 more months and we can’t escape it: we need this before the project is delivered.

Finally, when everything seems to be under control, someone subtly comes up to you and says: “hey… did you see that Narnia has a very strict data protection law!?”. Suddenly you have sirens and alarms ringing in your head. This is not a change of wind or a turning of the tide. That’s an iceberg. And one of the big ones! What now?

Now it’s time to investigate very calmly and carefully to be sure of what we’re doing. Worse than a delayed project is a project that breaks the law and puts our company and customers at risk.

While investigating, we realize that Narnia has an extremely strict data protection law, in which no customer data can leave national soil. Our entire system runs on Brazilians computers, with free traffic between countries. This iceberg is a big one and the simple project of 2 months is something that will require a change in the structure of the entire system of the entire company.

We even need to analyze how a requirement as complex as this went completely unnoticed by all the people involved in the project. This is the kind of thing that couldn’t go unnoticed and it was a pretty big flaw. We need to document what happened so that this doesn’t happen again, since, as you can see, the “easy” project has become a huge monster that made us completely reassess the structure of our entire system.

Maybe you’re thinking right now “no way, Letícia, that’s seems too unreasonable”. I know it seems… but things like that happen. A long time ago, on one of the projects I led, I made everything pretty. Soon after came the first problem. The second, the third, and so on. At some point I came across a mega iceberg. It was a huge problem that was going to delay the entire project flow and certainly impact the deadline. The project had many risks of not working out, the launch of this functionality was linked to very short external deadlines and there I was, trying to maneuver the Titanic. I’ve seen it happen to several developers in several companies.

Here comes the difficult part: being able to communicate openly and clearly what is happening. A huge iceberg heading your way is bad. But it gets even worse if the scout, ashamed of not having seen it ealier, decides not to communicate that it’s there.

When my iceberg was coming, crisp and clear in front of me, my first reaction was to panic. I was sure that I was not good for maneuvering this ship. That if this project was so chaotic (and late), I might not actually be the person to lead it. But as the old saying goes… “a calm sea never made a good sailor”. I realized that leading a project well was not leading a good project, but leading a project when everything goes wrong. I rolled up my sleeves and started dealing with my iceberg until the ship was back on course, safe and sound.

. . .

Just as knowing exactly how a ship’s buttons and controls work doesn’t mean you can actually maneuver it, this is also valid here, in our world: knowing how to program a complex project is not all the skill you need. As you can see, the rabbit hole goes much deeper.

As I was thinking about this talk and constructed this analogy, I started to think about what it all meant. If I am a captain, maneuvering ships through rough seas and hidden challenges, what can I do to become better? What skill can take me further and effectively become the best captain I can be?

When I started to reflect on this, a skill came to mind. Something I had never seen before as a key skill for my role, but the more I thought about it, the more it made sense. For me, that skill is empathy.

By empathy I mean:

There are two ways we can do this: the first one is the most known one called affective empathy. In this case, we share an emotional response. A clear example of affective empathy is when someone you love is suffering and you feel like if you were suffering yourself.

The type of empathy that I have seen as part of my work is the second type: cognitive empathy. In this type of empathy, we start to take on the perspective of others and make it our own. In this case, it’s necessary to recognize that other people have different tastes, experiences, and worldviews from ours.

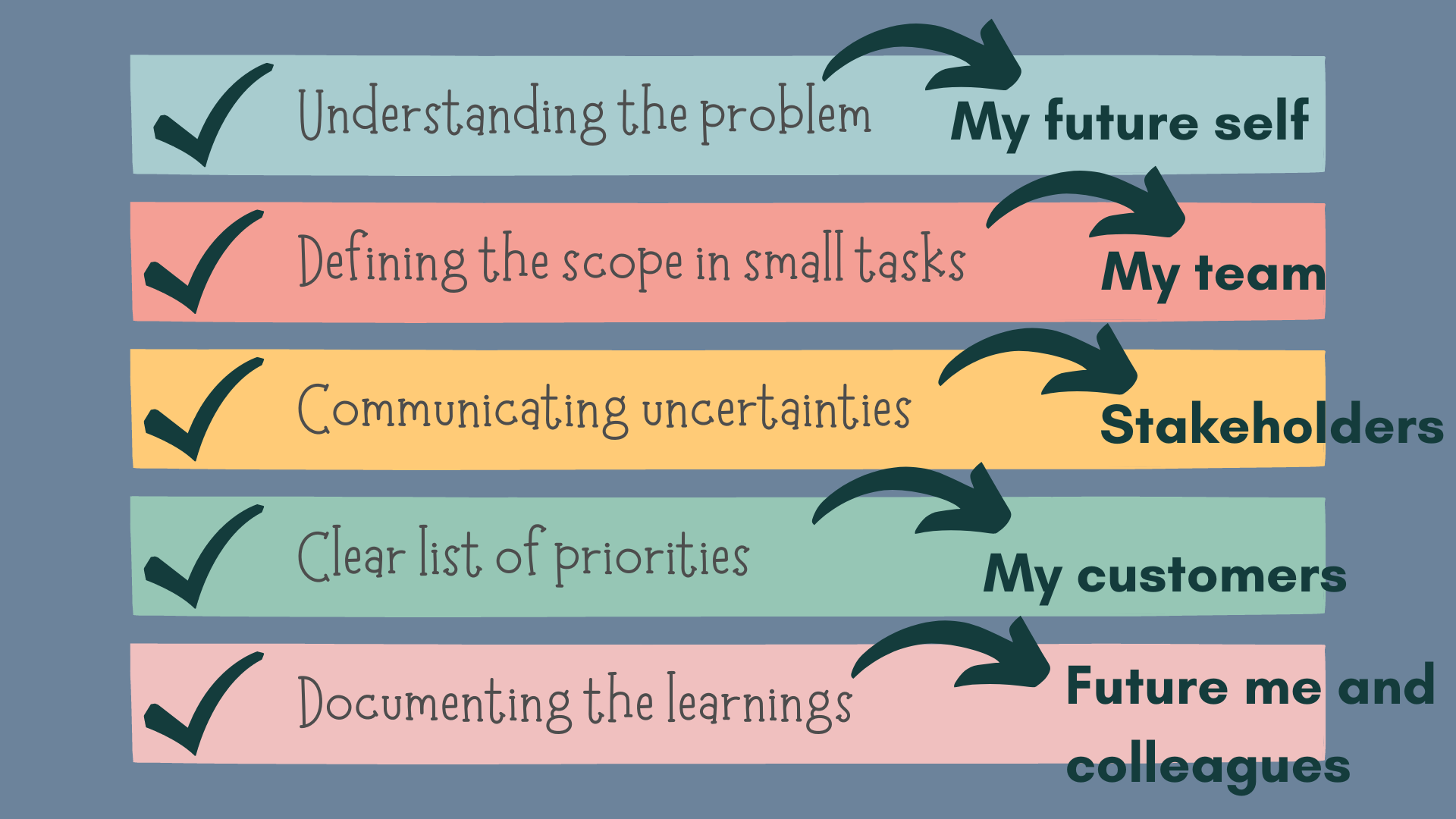

Let’s take a closer look at all the points we discussed when leading a project. Can you see empathy emanating from each of these steps?

When I said that I need to understand why I’m doing the task I’m doing, it’s because I have empathy with my future self. It’s only with relevant, challenging, and impactful projects that I’ll be able to advance my career in higher directions.

Not only that, but it’s only by asking and understanding the motivations behind a project that I can begin to understand reasons, analyze the choices behind each decision, and thus start building the necessary experience to one day do the same when I am in this position.

When we’re defining the scope and breaking down requirements into smaller, well-defined tasks, we’re showing empathy towards our team. Often, the person who defin the scope aren’t the ones working on a task. So having them well-divided, with clarity on what needs to be done and organized, is making sure you’re leaving your team in the best possible position to succeed in this project, even if you leave the project for any reason whatsoever.

And when we talk about deadlines, that extra time we add is nothing more than knowing that things happen, and giving space and time for people to breathe, work calmly, and have time to deal with any small uncertainties that may arise. Because you know they are more likely to happen when we are talking about long projects.

All of this generates good results for your team, even if it seems irrelevant at first.

Communication may be the point where you most associate with empathy, since communication is about thinking about the multiple teams and people involved in the project. It is knowing that all the people who will benefit from clear and effective communication are tied to the project with their own desires and anxieties, and that knowing what is happening, whether for better or worse, will make them better equipped to deal with the circumstances.

Similarly, clearly defininng priorities and ensuring that we can deliver something of value as quickly as possible is having empathy with our customer. If we are investing our time in building something to improve someone’s life, we want that problem to be solved as soon as possible, right? As developers, we may be in the best possible position to analyze what can actually be built first and faster.

Knowing how to analyze what is feasible and what is a priority within the context where you are is almost a superpower: you help your customer, you help your team, and you allow for more acute creative thinking, since you are seeing problems from a completely new perspective! All in a small act that may not take you more than a few hours to conceive.

When we document the learning we are having, we are empathizing with the future, both our own and that of people who may not even work with us yet. It is just when we decide to sit down, spend time thinking about our learnings, and documenting our discoveries that we can make the future better than the reality we are living now.

Ultimately, dealing with uncertainties will require a little bit of all the empathy levels we have talked about so far. Each iceberg in your path, whether big or small, is like a small project, with all the scenarios we have talked about so far.

So, what I am doing here, after all, is having empathy. In multiple ways, at multiple moments, and in multiple levels.

When you write good code, you are having empathy with the people who will maintain that code. When you spend your time giving good feedback to your colleague, you are having empathy with the professional that person can become.

When we introduce a new configuration in a system and it breaks and the on-call person wakes up in the middle of the night, with production broken and a sleepy brain… and then they cannot find a runbook that explains how to fix this problem… It’s the lack of empathy that causes frustration.

When we make a harsh comment during a code review, it’s the lack of empathy that distances us and creates barriers.

When a new person joins the team and is “thrown into the fire,” it’s the lack of empathy that pushes them out of this world.

And not only that… we also have to have empathy with who we were in the past.

Who has never come across an old code, which takes a weird turn and has unnecessary complexity, and thought: “this makes no sense! Why on earth did someone do this?”. We go, scratch our heads while our eyes fill with frustration.

At the same time, how many times are we writing a code and can’t avoid these curves and corners that we have add? How many times do we try to align different expectations and opinions in the code?

When we look at an older code and think about it, the reality is very different from when it was created. The knowledge and understanding of the subject today, which makes us see an easier path to follow, was completely obscure and unattainable a few months or years ago.

I, like many of you perhaps, always thought that empathy was a gift: either you have it, or you don’t. However, recent studies show that empathy is like a musical skill: some people are born with a greater vocation, but we can all train and improve.

There are countless books on developing and improving empathy, and I recommend “Empathy: why it matters and how to get it”. But I wanted to give some examples that I have experienced recently.

For example, I work with software that helps calculate sales tax. Rarely do I say this and the response is “wow, that’s interesting!”. But I like it a lot because it is a dense and complex subject, not easy to turn into code. However, after a long time working on this topic, it’s very easy to assume that people know as much as I do and it is very easy to start creating a product that is difficult to use.

To empathize with our customers, at least once a semester we hold sessions where all team members, whether newcomers or not, try to use our product from scratch, trying to think like a customer would. We take notes on which parts were difficult, which documentation was confusing, and which parts of the system didn’t make sense. In addition to generating a list of things we can improve, this exercise also helps us not to make a product for ourselves, who talk about taxes every day.

Because of all this complexity, we also have to have empathy for those who come later, as it is natural to have a slower learning curve. The other day a colleague commented to me that a certain part of the system was very obscure to him and he was always insecure about going on-call, as he would have to deal with problems. He wanted to learn more but found the documentation on the subject very dense.

Knowing that this problem was not uncommon, I proposed to my manager that we do a slightly more hands-on training. I took the part of the system that was the most obscure and introduced a very small bug in a test environment. To ensure that everyone was involved, I scheduled a meeting with the whole team and presented the problem in the same way a user of ours would.

The team formed pairs to find the problem, sharing techniques for finding the problem, tools that could be used, and which documents could help in this case. It was an interesting exercise in which everyone learned a little about how to find problems but we also managed to talk about the code in a much more practical way, since everyone had contact with it before.

. . .

Well, I hope it has become a little easier to understand how to apply empathy with your customer and your team, but there is still at least one missing piece here: ourselves.

We all want, in one way or another, to be better at what we do, right? And as I said at the beginning of the conversation… it is very easy, especially on a bad day, to forget everything we’ve done and how hard we’ve fought to get where we are. In 2020, I gave a talk (pt) where I presented the concept of the “Brag Doc”. This is a document that I write every semester, always highlighting what I want to achieve in the next semester and everything I did in this semester. I share this document with my manager and colleagues, so that everyone remembers what I did when it comes time to evaluate my performance.

What is this if not me having empathy with my future and my career? What good is it for me to make an effort if I don’t remember what I did or where I’m going?

For many years, technology was essentially a logical, technical, male field. “Hard skills” were what mattered and anything “soft” could only be weak, unnecessary, and even contemptible. But the reality is very different.

It’s more than time to realize that software development is a team sport as much as rowing. Google did a survey to try to understand what makes a team effective. The answer? How a team behaves is much more relevant than who is on the team. Teams need to be in tune to achieve the best performance and the only way to do that is to cultivate skills that go far beyond code. It’s cultivating empathy.

It is with empathy that we can build effective teams. It is with empathy that we can build truly delightful products. It is only with empathy that we can be who we are, because we know we will be welcomed.

The modern world is complex, beautiful, diverse, and dynamic. Today’s truths are completely transformed tomorrow. Nothing purely technical and cold can solve the problems we are trying to solve today.

Code is what moves us. It is our passion and what brings us here today, in this room. Programming is what makes us fall in love and want to build our careers. But it is empathy that transforms us into something greater. It is empathy that makes us evolve and go further. It is empathy that makes us, in fact, exceptional developers.

Cheers!

Letícia