What does it mean to test software?

Although we think of a software as being this one massive thing that does a lot of things, we can thing of a software as a huge pile of small functions that work together. A function is basically something that receives inputs, work with them internally and returns an output.

For quite some time now, I realize that explaining how I do the work I do as a software developer is really hard for people who has little or not coding background. Since I started working as a software developer one of my favorite things is trying to explain to my mom and her friends about the world I live in, in a simple and accessible way. So I decided to write a series of blog posts that will try to explain the world of software for people with little or not context on the field. In my mind, I call this “My mom’s technical handbook”.

A function is something that receives inputs, work with them and returns an output

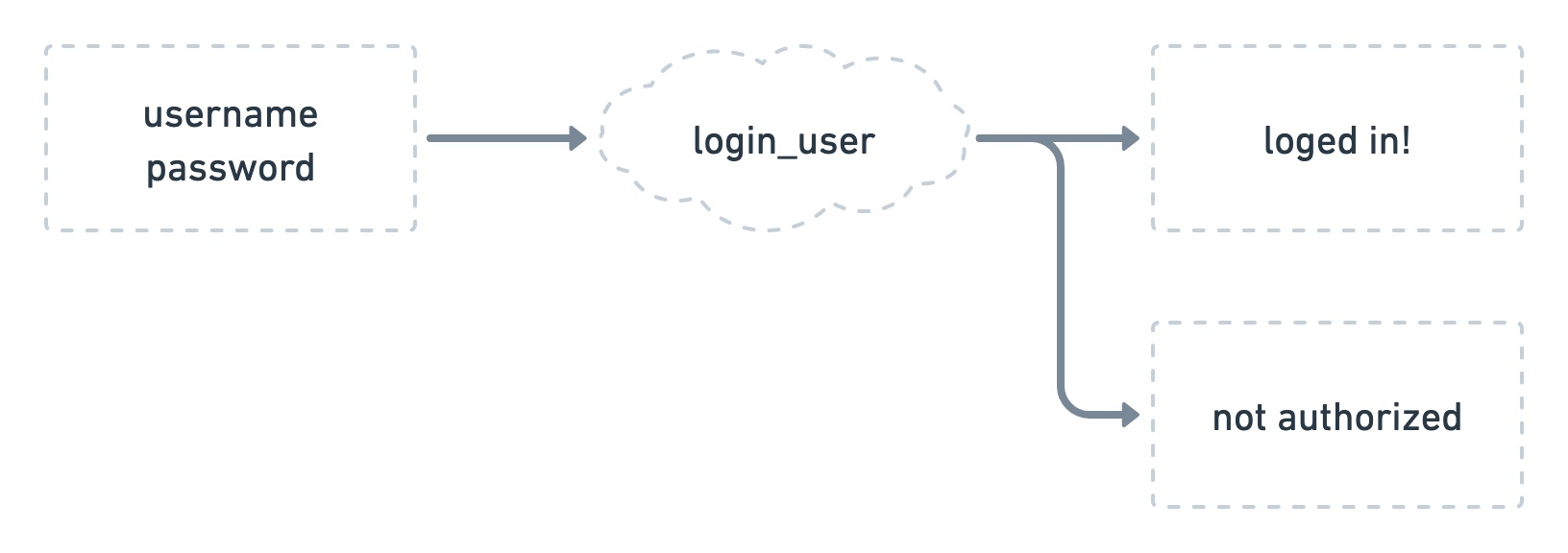

For example, when you type your username and password to try to login to a system, there a bunch of things that can happen but on the bottom of it all there is a function that receives the username and password and returns an answer: is this user logged in? The answer will be what we call a Boolean value: it will either return True or False.

The function is presented as a cloud and boxes indicate inputs and possible outputs

Testing the function

Now that we understand what this function does, we can use this knowledge to test the function behavior. The first obvious way of testing it is guaranteeing that a user that my system knows will be logged in when thy type the correct username and password.

We can create a user that can access the system, whose username will be geralt and the password is witcher123. We can do it, for instance, like the following command:

User(username="geralt", password="witcher123")

What do we expect now? If the user is known by our system (and the user geralt is), we expect that when I pass that username (geralt) and that password (witcher123) to the function that is called login_user will return True, indicating that the user is known by the system and thus, can be considered logged in.

The code for a test like this would look something like this:

assert login_user(username="geralt", password="witcher123") == True

If you notice, the code is very similar with us reading something out loud: you should assert that when login_user receives username=geralt and password=witcher123 this is the same thing (==) as True.

Test means checking other assumptions

Now that you understand how this test works, do you think this function is actually tested? Believe it or not, it is not! We just checked one possible outcome for the function, but we did not guaranteed that a random person can’t access the system. Or that a user with a wrong password will have access to the system. So to test a function - properly testing it - means that you should check other assumptions and other behaviors, checking for possible outcomes (and errors).

So now, we can do a similar test, but this time we can check if the user passed a wrong password, the function would return False instead of True:

assert login_user(username="geralt", password="another_password") == False

Or if another user that the system doesn’t know can’t access the system neither:

assert login_user(username="yennefer", password="vengeberg") == False

As you can see, the idea of this test is to verify the behavior of the function. This type of test is called unit test. As written on the Wikipedia:

The goal of unit testing is to isolate each part of the program and show that the individual parts are correct. A unit test provides a strict, written contract that the piece of code must satisfy. As a result, it affords several benefits.

As you can imagine, this won’t guarantee that the end result of the whole system is correct, but if each part of it does what it is suppose to do. This is the minimum way of testing you system, but there are many, many, others.

So simple, why test it?

This may seem pretty simple to some of you at this point. Like, why test something so simple? You could manually test it and it would be fine. Indeed, it seems simple when we are considering just a single function. However, the more complicated the software is, the more complicated it is to guarantee that a change in the system won’t break the behavior of something down the line. Guaranteeing that each small function is working properly decreases the chances that the whole system will be broken by a new development.

As time goes by, the software we build doesn’t look like the nice diagram above, but it probably look something like this:

How can you guarantee that if you change one part, the others won’t start failing? If the functions are tested well enough, making changes in the system is easier, because you can identify things that were broke before the changes ever get to the final customer.

And if you notice, the test doesn’t care what happens inside the login_user function. It cares if the result of the function is correct. So if you changed the database from where you check if the user exists or if you optimized the search, it won’t matter to the test. The only thing that matters is that the end result is correct.

Testing is the process of executing a program with the intent of finding errors [0]

Testing saves you money

When you are searching for errors while developing the code, you are actually avoiding errors to surface on your user. This also means that the cost of change something is much smaller than it would be without the tests. With time, the costs of errors unsolved become exponentially higher and testing fundamental for identifying errors as soon as possible and avoid this costs. [1]

There is also another cost for errors that we can’t really measure: the cost of loosing the trust of a customer that can’t work with your system.

Let’s imagine that you don’t have any tests and have to change in the software. The changes are made, you manually test the part of you system that you think is involved and now the changes are available for the user. When your customer access your system, they realize that something is not working properly. Now there is a cost of customer support to listen and report the customer error. The developers will spend some time debugging the problem until finding the root cause, than fixing it and then deploying it again. And finally your customer support needs to let the customer know that the problem is fixed.

If the system is well tested, the developer can avoid the error and all these costs (time, people) by catching the change of behavior is a failing test. Before the code ever get to the final user, the developer could figure out what is wrong and the test will help point out where the error is. And the best part: your customer does not see the error and continues to trust in your software. Who can put a price of confidence of a customer?

How and when to test?

Because tests are your most reliable asset on the eternal search for errors, they should be ran constantly. Thus, they should be automated and checked every time change is being added to the system.

The first thing you need to check when adding a change is that the existing tests are not failing. This is important because you want to guarantee that the changes being made are not affecting the system. So tests should never be deleted or changed - with very few exceptions to this rule. That’s why a lot of projects include automated systems that block new changes to be added if the tests are failing.

At the same time, you need to guarantee that the functionalities are tested and that they are tested correctly. This will help in the future, when new functionalities potentially change this part of the system.

Don’t forget to test what your user see!

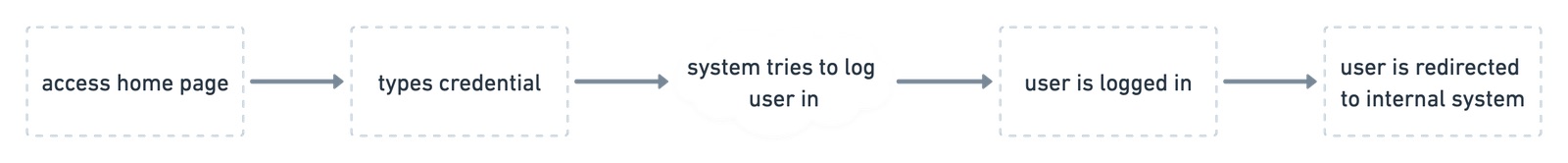

On the example above, testing if the login_user function works, doesn’t guarantee that the user is actually going to your website, typing their credentials and then redirected to the restricted part of the system. To do that, you need another type of test, onee that will actually go through all the flow a user would, verifying if the system is working with all pieces together.

This test is not checking the behavior of a particular function but rather what the user actually sees

This is type of test that will actually go through the system as a customer would, and they are much more complex than a unit test. There are variation on how this test is called, but the thing is: it is also important to actually test what your user is actually seeing and not if all the small parts are working.

Stress your software!

With both cases presented above you can verify if you test does what it should do correctly and if what the final user is seeing is what you want them to see. Now we need to see if the system performs the same way under different types of problems.

For instance, one common problem is a software being broken due to a massive number of requests from users at the same time. One possible test to check if what the system can handle is stress the software by making thousands of requests per second, simulating that you system is crowded and see how it behaves. Chances are that it will probably break at some point, and you must define which and how could you could increase the load that it can handles, or if the load is good enough for your case.

Let’s take an example. Imagine that you are doing a system that helps people to fill their annual income taxes. Most users will spend most of the year not accessing your system, but then when the deadline approaches they will all come back to your software! At the same time, you need guarantee that the system is not consuming all the resources all year long. Otherwise, you will have a huge cost for having a system prepared for a high number of users that will likely come just in a single month of the year.

Other types of stressing your software is testing what is the typical response time of the system. When you see that the average response time is 200ms, that doesn’t mean anything. We know from statistics that a mean can be very far from the reality. We need to understand the maximum wait time for the vast majority of requests. It doesn’t matter that a lot of users is getting the results really quickly if another user is waiting 5 seconds to get their response.

The exterior doesn’t matter

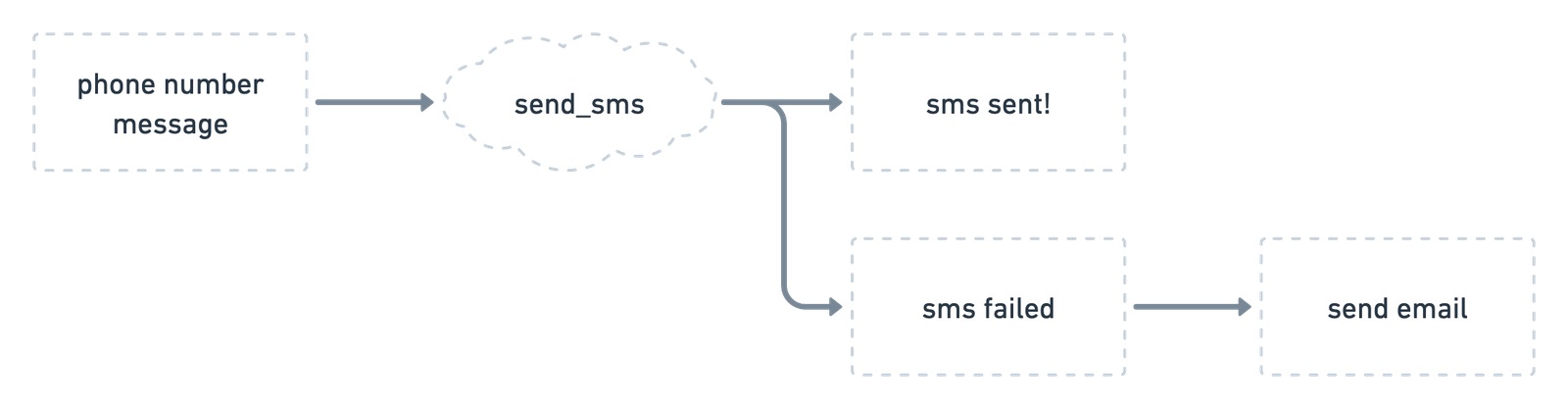

Imagine that you are building an integration with an external partner that will send an SMS every time a user signs up to your system. The integration is pretty simple: you pass a phone number and a message and it will return a message sent! to indicate that the message was successfully sent. If the SMS failed, the system will send an email to the user.

sms = MyPartner.sms(phone="123456", message="Hello, user!")

# sms will be either "sent" or "failed"

The system will send an sms, if it fails, it will send an email

However, every time you run this command, the company MyPartner will charge 10 cents. As we’ve seen, you want to test that the system is correct, but we don’t want to be charged 10 cents for every test we run. And tests should be ran all the time! So what to do?

If you notice, you don’t actually care in your test if the SMS was actually sent, right? You care if the system called this function and if the system will send an email if the SMS function failed.

What we can do is mock this function. This is, we can basically create a fake function that will return “sent” or “failed” so we can test the system behavior.

So, a Mock is basically a fake system that will return what you want for purposes of testing. The idea is to mock the parts of the system that are external and you only care about possible outputs.

For instance I can mock the return value and make it always return “failed”. This way, I can test if after this call, the system will actually send an email or not. And because the original (not-mocked) function was never called, I won’t be charged 10 cents 🙂

sms = Mock.sms(return_value="failed")

# sms will ALWAYS be "failed"

Can you see the possibilities? Now that you understand how mocking your system works, you can actually use it to develop parts of you system that works with other parts that aren’t built yet! If you have an agreement on inputs and outputs… you can build things in parallel!

Hope you enjoyed this post technical but not full of code 🙂. This is the first from what I am hoping to be a series of them. Hope you have enjoyed, please leave your feedback and suggestions for new topics.

References

[0] GJ Myers, C Sandler, T Badgett. 2011. The art of software testing

[1] JC Westland. 2002. The cost of errors in software development: evidence from industry. The Journal of Systems and Software 62 1–9.

–

Photo by Deva Darshan in Pexels

❤Cheers!

Letícia